By the turn of the 20th century, Thames A-Raters were in their heyday. Races were hotly contested and drew crowds of spectators along the river’s “Promenade.” The class’s popularity was boosted by the prestige of its events and the drama of its racing. Bourne End Week, especially, became the unofficial national championship for A-Raters – the only place one could see a dozen of these leviathan dinghies dueling on a river scarcely wider than the boats are long. It featured daily class races and culminated in the Queen’s Cup, which only the A-Raters sailed for, adding exclusivitysail-world.com. The Thames Champion Cup (first awarded 1887) also became part of the lore – originally a single race at Surbiton, it later turned into the week-long series trophy at Bourne End by 1900raterassociation.co.uk raterassociation.co.uk. Wealthy gentlemen helmed in these regattas, often hiring skilled local sailors as crew. In the early days it was very much a “gentleman’s sport,” with owners lounging to windward while paid hands did the heavy work of running enormous sails and shifting ballastsail-world.com. Over time this dynamic changed – today most boats are owned by clubs or syndicates of amateurs – but the tradition of demanding, high-crew-work sailing remains.

Culturally, the A-Raters added a dash of glamour to river life. Clubs like Thames SC, Upper Thames SC, and Tamesis Club (founded 1885 in Teddington as a spin-off from TSCthames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk) all vied to host memorable regattas. Royal and aristocratic connections were common: besides Queen Victoria’s involvement, the UTSC presidency was held by nobility, and prominent figures like Lord Desborough and others took an interest. As noted, the social diary of Edwardian high society listed Bourne End Week alongside events like Henley – it was a place to see and be seenthedailysail.com. One can imagine ladies with parasols lining the banks and brass bands playing as the Raters, dressed in colourful racing flags, skittered down the Thames. (In fact, an old photo of TSC around 1897 shows nearly every boat bedecked in bunting – possibly in honor of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee – making a festive scenethames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk.)

Queens Cup Winners 2024 & 2025 Osprey

On the technical side, the “golden era” saw relentless experimentation. Sail plans were in constant flux. The earliest A-Raters carried lug sails (four-cornered sails hoisted on a yard)raterassociation.co.uk. By the 1890s-1900s gaff rigs and gunter rigs (a kind of high-peaked gaff sail) were common, allowing a tall sail to be set on a relatively short mast – useful for ducking under bridges or lowering sail quicklyraterassociation.co.uk. Around 1919, one boat – Saucy Sally (Hope design, built by Burgoine 1906) – made waves by adopting a Bermuda rig (single triangular sail with no gaff) at a time when most competitors still used gunter or gaff. Her experiment was so successful that others swiftly copied itthames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk thames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk. By the 1920s, Bermudan rigs took over, and the class became one of the first to push mast heights to then-unheard-of levels. Even in the ’20s, A-Rater masts of 38–40 ft were reported (on 25–28 ft hulls)thedailysail.com. To achieve this, innovative construction was used: some masts were built in a composite of wood and aluminum – an early example of mixed materials to get both lightness and strengththedailysail.com. After World War II, one syndicate even tried a 47 ft mast – nearly twice the boat’s length – in the quest for more power aloftthedailysail.com.

Hull designs also evolved. As designers learned the quirks of river racing, features like lifting centerboards (centerplates) became standard in lieu of deep keels, so the boats could navigate shallows and “shoot” up to the river’s banks out of the currentthames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk. Many boats retained a shallow fixed keel or ballast bulbs for stability, but with much reduced draft compared to seagoing yachtsthames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk. Some early Raters (like Burgoine’s Ruby of 1870) were later modified with elongated sterns and raked bows to increase waterline length when heeled – essentially the first use of long overhangs on a racing yacht, a trend that also appeared in big yachts of the era thames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk thames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk. By 1900, most A-Raters had the “arrowy” look: long ends, beam carried well aft for planing, and flat sections amidships. They were true skimming dishes, sitting low in the water and speeding over the river’s surface when the breeze allowed thamessailingclub.co.uk.

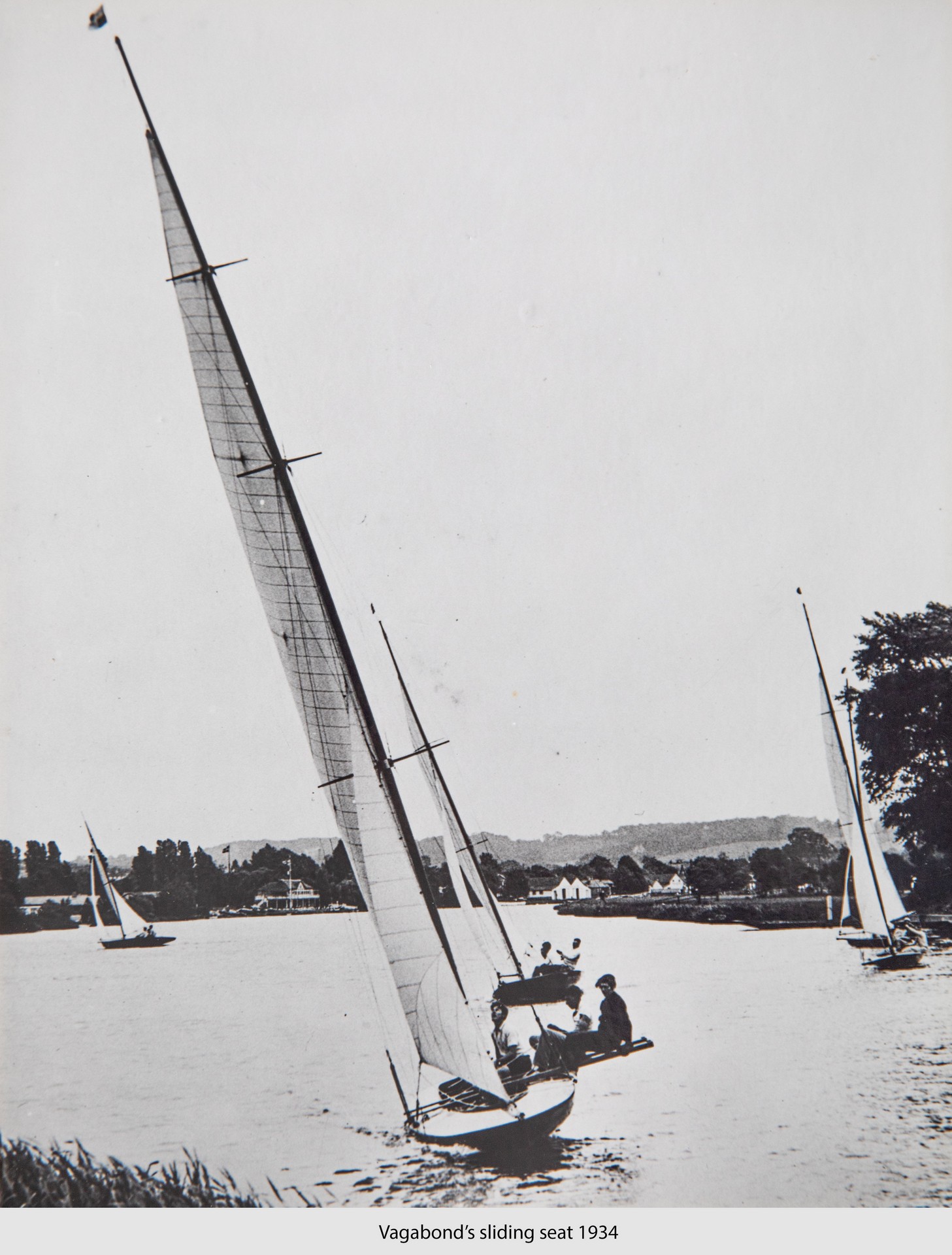

Perhaps the most remarkable innovations came in the 1930s, as the class sought ways to carry those huge sails in stronger winds. Beecher Moore, an American-born dinghy champion in Britain, purchased the aging Vagabond in 1934 and set about turbo-charging herthames-sailingclub-history.thecomputerguy-it.co.uk thamessailingclub.co.uk. He and his crew (including the young Peter Scott, who would later become an America’s Cup sailor and famed conservationist) tried something radical: they rigged a trapeze for the crew to hike out. This crude harness – basically a wire to the mast with a rope “handle” and big knots to grab, nicknamed the “bell rope” – allowed a crew member to hang bodily over the side, counterbalancing the heeling force of the sailsthamessailingclub.co.uk thamessailingclub.co.uk. As Beecher Moore recalled: “I used a loose wire which went to the hounds (masthead)… with big knots in it… Bill Milestone was my first crew to hang out on this… it gave us great success.”thamessailingclub.co.uk thamessailingclub.co.uk It was the birth of the trapeze in dinghy sailing – years before the device was (briefly) adopted and banned in the International 14 class in 1938. In fact, Peter Scott, while crewing on Vagabond, improved the idea by adding a proper harness for safety, and with that he and John Winter won the 1938 Prince of Wales Cup (the 14’ dinghy championship), heralding the trapeze’s potentialthamessailingclub.co.uk. Not to be outdone, Moore also fitted sliding seats on Vagabond – up to three planks that could extend out each side, allowing all crew to hike far outboard (an idea borrowed from sailing canoes)thamessailingclub.co.uk thamessailingclub.co.uk. This made Vagabond of the ’30s a floating laboratory for dinghy performance. Thanks to these measures, her 45′ mast could be carried even in strong winds, and she became nearly unbeatable in her revived career. These innovations, though not immediately universally copied, cemented the A-Raters’ reputation as trend-setters. Many features of modern high-performance dinghies – trapezes, hiking racks, light hulls with big sail area – were pioneered on the Thames long before they spread to the wider sailing world.

Thames A-Raters racing on a narrow river course (Horning Three Rivers Race). Their towering rigs capture wind above the trees, while crew hike out to balance the immense sail force. The class’s elegant lines and speed continue to awe spectators, just as they did in Edwardian times.thedailysail.com thamessailingclub.co.uk

Despite the excitement, the 1920s–30s were also a time of challenge for the class. Competing dinghy classes emerged with more convenient size or rules – notably the International 14 (a two-man dinghy) attracted youth and innovation during the interwar years. B-Raters (the smaller class) virtually died out by WWII, as one-designs and modern dinghies took their placeraterassociation.co.uk. Even the A-Raters saw declining numbers. By the late 1930s, active racing at Upper Thames SC had dwindled, kept alive mainly by devoted individuals like Moore. When WWII broke out, many boats were laid up, and some were lost or disposed of.